Editor's Note: This is part of an occasional series of stories about people whose paths to Mid-Missouri started with immigration and how they made the journey from their home countries.

In 1996, Rexroy Scott was a 19-year-old soccer player in a small, hard-working community on the northeast coast of Jamaica.

He quickly found himself facing American culture head-on after a Jamaican professor gave the soccer coach at Lincoln University a tip about a young defender worthy of a scholarship.

Life in Jamaica

The village where Scott grew u lies in St. Mary Parish and sits in the shadow of a high-end resort. The people of Hamilton Mountain, like many areas in Jamaica, work mainly in agriculture and tourism. Within miles of each other, glitzy resorts are contrasted by poorer, working-class communities.

“It could basically be next door you’re gonna find a five-star, all-inclusive resort. The income level is a stark difference,” Scott said. “Income inequality is a huge problem here (in Jamaica). There are wealthy people, there are poor people, there is not a lot in between.”

Life in Hamilton Mountain is typical of many small Jamaican communities, where residents are close.

“You know, you’re not just raised by your parents. There are other people out there that you have to be somewhat accountable to ... . I come home and I have to go visit them, and they’re old people now,” Scott said jokingly.

Having a large number of parental figures put pressure on Scott’s shoulders, as he was known to be both academically and athletically gifted.

“There are countless people who don’t live in my household that I feel if I did something wrong, it would be a disappointment to them,” Scott said.

The education system Scott grew up in places children into defined sections through testing at a young age. Scott, being one of the few males who tested highly, felt that pressure to succeed from a very young age.

“Smart kids go to smart schools, and not-smart kids go to not-smart schools. And they test you at 10 years old, between 10 and 12; and depending on what your score is, you get to go to a school of your choice,” Scott said. “It could crush a kid.”

Culture shock

Coming to America at 19, Scott faced a double dose of culture shock as he arrived in mid-Missouri.

“A high school student now leaving to go to college, there’s a lot of apprehension, new people, you know, new friends, new environment,” Scott said. “For me, that was multiplied by 10 ... lots of new things to get used to.”

Coming to mid-Missouri, Scott found a very different culture than he had come to expect from America. It wasn’t skyscrapers and subways.

“It was a case of, you know, what you see on TV, and your idea of what America is — North America is — versus the reality now of what you’re going to actually see,” Scott said.

One of the biggest sources of culture shock for Scott was the lack of a focus on community in American culture.

“I could live in my subdivision in Columbia and not speak to my neighbor for six months. That doesn’t happen” in Jamaica.

“You don’t, you don’t get up and say good morning to everybody. Because they look at you weird, like, random guy, greeting me in the hallway.”

Scott has found that unlike the big American cities with established Jamaican communities, mid-Missouri culture forces immigrants to be self-sufficient.

“Here I am in the middle of nowhere with a very limited support system. So the options, it’s sink or swim. If I can survive in Hamilton Mountain with a single father, I’m sure I can survive in mid-Missouri.”

Since Scott moved to America, the Jamaican community in the area has become well established. Much of this is due to the Jamaican pipeline of track and field talent to Lincoln University.

Under Jamaican coach Victor “Poppy” Thomas, Lincoln University has built a dominant track dynasty over the past 20 years that has helped the local Jamaican community bloom.

The start of Jerk Hut

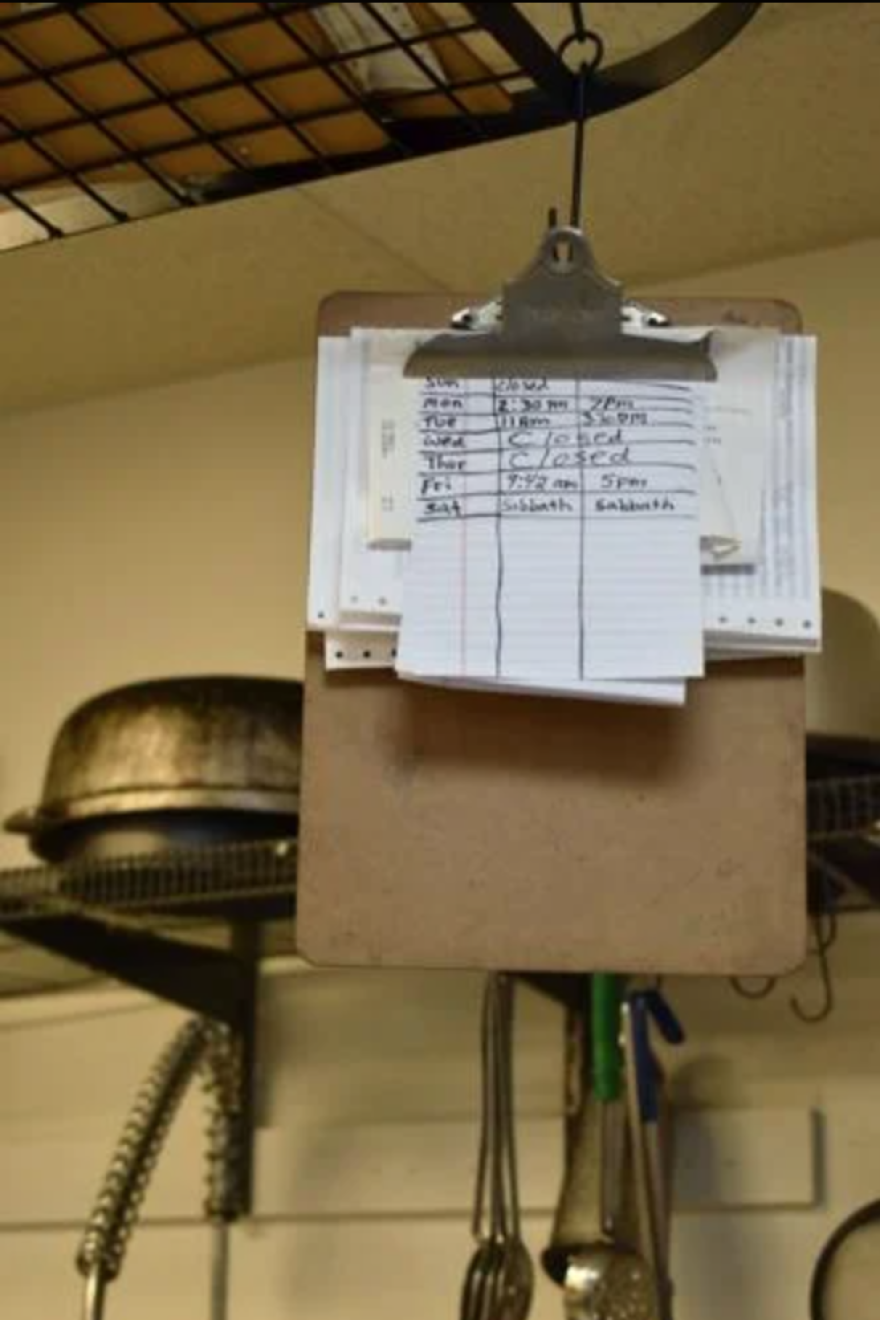

During his time in mid-Missouri, Scott has become an information technologies professional at MU and a co-owner of Jamaican Jerk Hut. Jerk Hut boasts locations in Jefferson City and Columbia as well as a popular food truck.

It all started with the small Caribbean community in Jefferson City.

"When a Jamaican goes somewhere, they have friends and family that they know will ask for information, and you make it easier for the next guy to get in,” Scott said.

Colin Russell is one Jamaican who immigrated to mid-Missouri with the help of Scott. Russell grew up in Oracabessa, Jamaica, a town just a few miles from Scott’s native Hamilton Mountain. The pair have been friends since primary school. They played soccer together at Lincoln and now co-own Jerk Hut.

“We were both athletes, you know, we met on the playground. We really became friends after I beat him on the track,” Russell said. “I got a call, and he’s (Scott) like ‘Hey, you wanna come up and play ball? You can get a scholarship.’ ”

Russell moved to America just a year after Scott, and the two became even closer as friends in a small, tight-knit Caribbean community.

“We just play ball, do schoolwork and hang out. It wasn’t a lot of us, so we even got closer,” Russell said.

Over the years, the Jamaican community around Lincoln University grew, and Scott was at the forefront of bringing people together, with weekly parties uniting the Caribbean and African communities in Jefferson City.

“So we come together, the gatherings will get bigger and bigger every week,” Scott said. “We’d put our funds together and go to the Gerbes closest to us and buy meat and seasonings and stuff and would cook different meals. It kind of became a block party.”

Based on the success of those block parties, Scott and some of his friends had an idea.

“I think it was my wife who said, ‘Why don’t you guys sell this stuff at homecoming? Because people love it when you guys do it,’ ” Scott said.

“We went to homecoming and sold all the food in ... less than an hour.

Scott proposed that they sell food regularly at festivals and events. Some of his friends decided not to go that route, but Russell bought in immediately.

“I’ve always had the entrepreneurial type thing,” Russell said, “and it’s something else to do, especially during the warm months when school’s out.”

After selling out of tents at Lincoln University homecomings and multicultural festivals, Scott and Russell gained a business license in 2003. The pair set up a food truck with their friends in a historic area of Jefferson City that used to be a hub of Black-owned businesses in the 1980s.

For the pair of young immigrants, finding a recipe for jerk chicken that appealed to their customer base was an adventure, and one they took on happily.

“I wasn’t a great griller. ... I told him, ‘I don’t have the expertise,’ and he’s like, ‘Neither am I. Let’s play around,’” Russell said.

“I tell people all the time: I’ve burnt up a lot of chicken and pork.”

Sharing food and culture

Jamaican Jerk Hut is an important part of the Jamaican community in mid-Missouri. It is a place to gather, eat familiar and sometimes hard-to-get food, and find people from your own culture in a place where that culture isn’t especially prominent.

Part of the reason Russell and Scott started cooking with their Caribbean and African friends in the first place was to find a taste of home.

“There was no access to our foods, so you make it yourself,” Russell said. “It was whatever ingredients you can find, so that you can get it as close to home as possible.”

For Scott and Russell, serving Jamaican food is more than just giving Jamaicans a taste of their home island — it’s a way to share their culture.

“I see food, it’s something common between every culture, right? Everybody eats, and everybody prepares food and eats,” Scott said. “The ways we either prepare, serve and consume our foods have served as, in my opinion, a conversation starter.”

Scott sees food as a common ground to meet people and understand them, despite the communication gaps that may arise between those of different cultures.

“Rex cares about people, you know, and that’s probably why we’re such good friends,” Russell said.

By understanding food, Scott believes that people can better understand each other and the history of their cultures. He is fascinated by barbecue culture in America and loves to share the history of jerk chicken with his customers.

“You kind of start conversations that way,” he said, “and you get to know people that way.”