If you’re looking for timely cultural criticism, you might more easily find it on YouTube than through a digital or print article

“When I was first writing blogs, the only people that would see those blogs were people who were already following me for some reason,” said writer Jacob Geller. But since becoming a video essayist, YouTube’s algorithm has allowed him to “break containment,” as he puts it.

While Geller notes that there are many negative aspects to such algorithmic recommendations, it has allowed him to reach millions of viewers.

“Something that is kind of amazing about it is it has allowed me to make these things that seem incredibly specific and then find that actually a lot of people have the same niche, specific interests as I do,” said Geller.

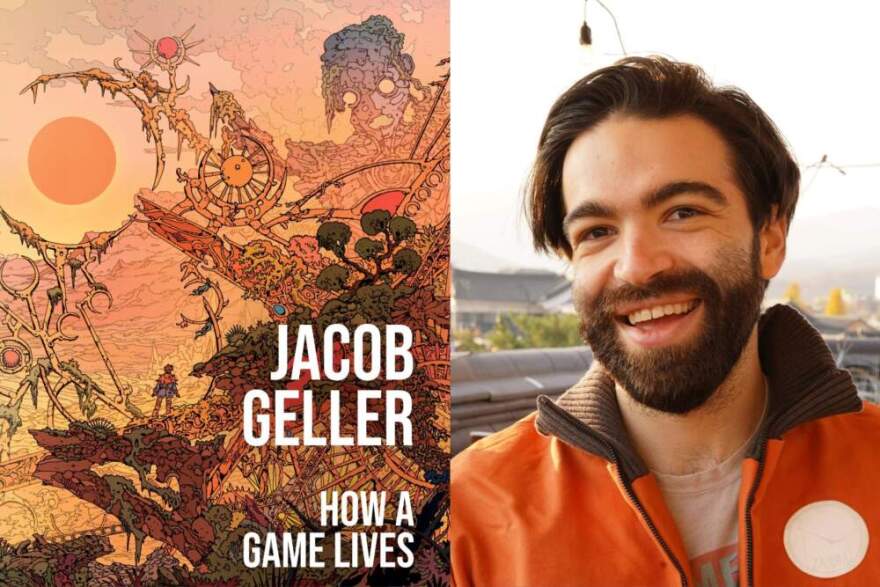

Geller collected the transcripts of some of his videos into a new book entitled “How a Game Lives,” out Nov. 19. He took the opportunity to update these essays with extensive annotations. He also commissioned contributions from other writers, such as novelist Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah.

“I always want an essay of mine to kind of open a potential avenue for analyzing something that someone hadn’t thought of,” said Geller. “Each essay that I’ve written now has a new afterword by a different author that is responding to the themes of the essay.”

Geller sees his work as continuing to an ongoing conversation about art, drawing from literature, film, TV, and — most characteristically — video games.

“Games are kind of the point zero that I build from,” said Geller.

“Most games have a narrative of some sort and sometimes that’s just communicated through dialogue between characters,” he said. “But also games have mechanics. They have specific ways that they make you interact with the world. You’re having to make decisions in a way that you can’t do in a book. And it makes it really interesting to analyze.”

5 questions for Jacob Geller

You’ve explored the military shooter franchise “Call of Duty” several times. You are interested in the meaning of violence in games. Why?

“Most games involve violence in some way. It is kind of the main verb that players often do, whether it’s shooting or slashing with a sword. And for a long time, us in the video game discussion sphere have been kind of scared of talking about it because violence was used to condemn video games. You know, now, and especially in the ‘90s and early 2000s, shootings were connected to the perpetrators being gamers. Because of that, it became almost the third rail that we didn’t want to talk about in the chance that someone used it to then say, ‘This is why video games shouldn’t be allowed to be made.’

“But I think that we can’t ignore that ‘Call of Duty,’ which is routinely the best-selling game of the year, is an incredibly violent series, specifically, a militarily propagandistic series. Not just that it’s convincing players to shoot people virtually, but that it is imparting all sorts of ideas of what the role of the American military is, which I find much more frightening than the idea that video games might somehow just cause a player to become violent in real life.”

When you take one of these big topics, how long does it take to make one of your videos?

“It takes quite a long time. Playing a game in itself is often not a short experience. A movie might be two hours long. A game could be 50 hours long. More and more, as I have gotten into researching these topics, I will play a game and then read multiple books on the subject.

“I made a video about the ‘Call of Duty’ series ‘Use of Torture,’ and that included reading several, you know, textbooks essentially about torture and how it is used in different places. And so I would say, usually it is at least two months on kind of a rolling schedule of playing, thinking about, researching, writing, editing. I’m often working on multiple videos at once because YouTube likes for you to have a kind of release schedule.”

We’re talking to you because you have a paper book out. So why come back to the ancient technology of the physical book?

“It does seem like a regression, right? To go from the amazing sparkly world of YouTube to books. One of the overwhelming feelings I have working on the internet was when the internet started, we kind of talked about it as, ‘Oh my gosh, the internet is forever. Anything that goes there will stay there for all time.’

“That is not the case. You know, websites can change their content guidelines, they can shut down, they can make themselves unsearchable from AI tools or algorithms that are not conducive to people finding what they’re looking at.

“And especially in the world of games writing, so many websites have gone bankrupt and all of their archives have just disappeared. So I have really found an appeal in owning physical things, whether that’s vinyl of the music I love or books of things that are even available in other places. And so by kind of making this book, I was like, I can archive my work and I can also make it more beautiful. I can include art. I can go back and look at the ways that my thoughts have changed. But it really is this feeling of anything digital slipping through our fingers if we’re not actively trying to preserve it.”

Your book is called “How a Game Lives,” and you’ve noticed that there are many ways a game, like a video, can die. It can be delisted by a store online. A once-popular online game can vanish from servers overnight. How do you hope your work here can preserve in this age when things come and go?

“I think some of the most important records of art that we have is how people respond to it at the time. You know, it’s wonderful to see a painting, but it’s even more wonderful to understand what that painting meant when it was released — what people’s reactions were to impressionism or to cubism or anything.

“And games are very much the same way. Modern games are built on the back of old games. It’s a very iterative medium. But if we aren’t able to remember what people were talking about when those first things came out, then we end up just kind of having the same conversations over and over. And so what I really want to preserve is this idea that people have always been talking about games as art and treating games as art. And if we can remember that, then we can move forward in the way that we think about them and analyze them.”

Is there a current or previous generation of cultural commentator you return to a lot?

“My favorite writer is Robert MacFarlane, who’s a nature writer. He’s written the book ‘Underland.’ ‘Is A River Alive’ is his new book. He explores caves, rivers, oceans, seas. But the thing that I love about him is that he just seems to have read everything and talked to everyone.

“So he is able to make these incredible connections between the environment and storytelling and history in a way that is mind-bogglingly connected. And that is the very high bar that I have set for myself. I would like to do that with games, stringing out that web of connections to show everything that they’re related to.”

____

James Perkins-Mastromarino and produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Perkins-Mastromarino adapted it for the web.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2025 WBUR