At the World Bird Sanctuary near St. Louis, injured birds of prey are rehabilitated at the onsite raptor hospital. Some are released back into the wild, and many that can’t survive on their own stay at the sanctuary for life. Unfortunately, some birds that come into the hospital are too sick to survive - and staff say avian influenza means they’re seeing more of those cases.

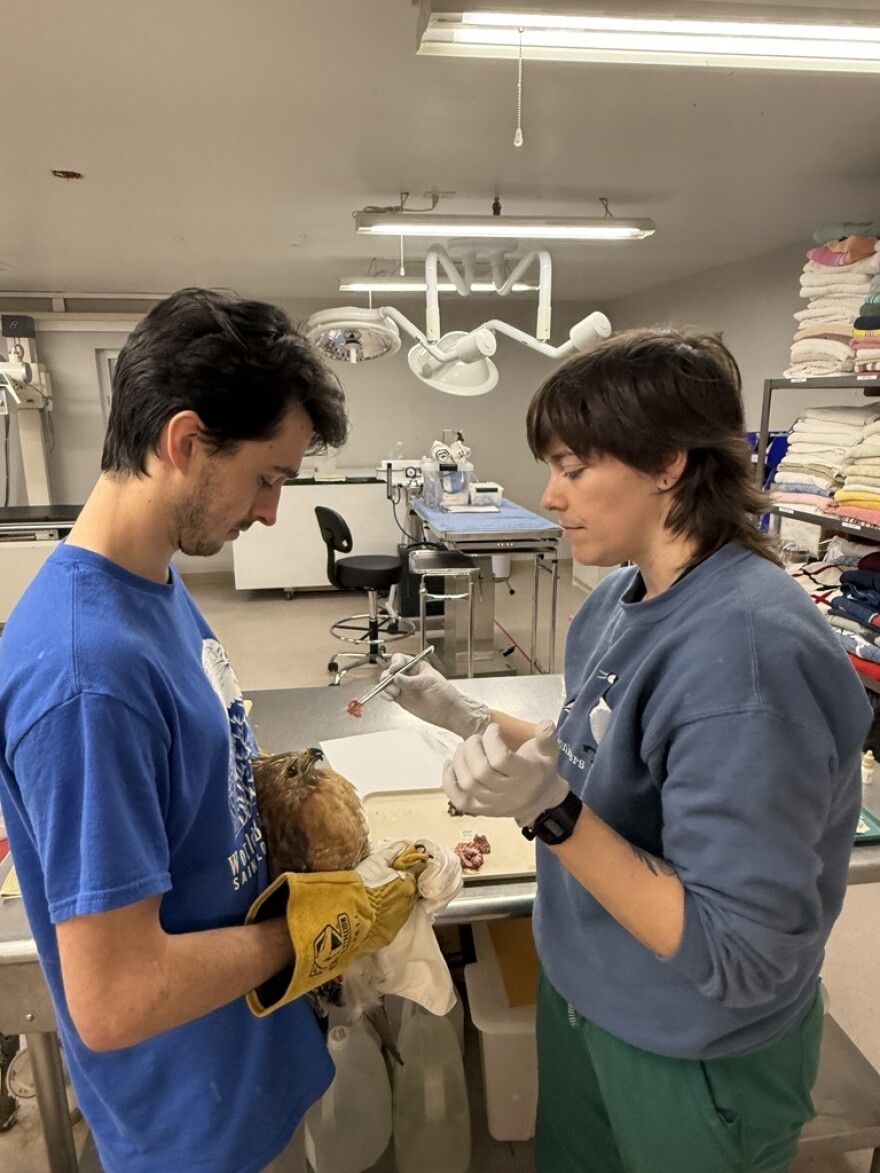

Kira Klebe is the director of rehabilitation for World Bird Sanctuary. She’s worked at the sanctuary since 2018, and said many things have changed because of H5 avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu. Studies show that H5 avian influenza is highly fatal to raptors.

“Nationwide for raptor species, there have really only been a handful of survivors at facilities anywhere, which is really sad to see,” Klebe said.

An outbreak of H5 avian influenza was confirmed by United States health agencies in mid-2024. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the public health risk is currently low - but states are still monitoring the progression.

The Missouri Department of Conservation says bird flu doesn’t present an immediate health concern. Deborah Hudman is the wildlife health program supervisor with MDC. She said avian flu cases in waterfowl have dropped off significantly since the holiday season, but rates have been rising in raptor species - particularly cases of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, or HPAI.

“Initially, it was primarily the geese and ducks and other waterfowl species. And now we're seeing some of the raptors, right? So they're predating on the carcasses, and so we're detecting some of that [HPAI in raptors],” Hudman said.

In raptors, avian influenza causes severe neurological symptoms and can be extremely painful for the sick bird. Klebe said that infected birds show signs like dilated pupils, low awareness of surroundings, twitching and wheezing.

Because avian influenza is so deadly and catastrophic, it is common practice to euthanize any bird that has avian influenza. Klebe said the sanctuary’s protocol is to euthanize any avian influenza patients that come into the hospital.

“We are currently electing humane euthanasia for all avian influenza patients, because pretty much all of them do just die between 24 and 72 hours,” Klebe said. “There is no treatment. There's nothing that can alleviate the symptoms. So all we can really do is give them the gift of a painless death.”

New protocols aim to protect sanctuary birds

In order to prevent avian influenza from spreading amongst birds who come into the World Bird Sanctuary, Klebe said staff has implemented a wide variety of protocols. When avian flu cases were first reported in the U.S. in 2022, Klebe said the sanctuary began quarantining birds suspected of having avian flu in a makeshift quarantine space.

She said now that some health officials say bird flu is likely here to stay, the sanctuary has built a dedicated quarantine facility where all patients suspected of having avian influenza are held.

“[We’re] trying to make sure that we were not bringing any potentially avian influenza positive patients onto our property. Just because we do have over 175 permanent resident birds here, we see over 770 patients a year, so we really didn't want to expose anyone else to that risk,” Klebe said.

As a result of the avian flu outbreak, Klebe said agencies like the Missouri Department of Conservation ask bird rescues to implement heightened biosecurity protocols to prevent the spread of avian flu within wildlife rehab facilities. Klebe said the sanctuary has added disinfectant foot baths at the entry and exit points of every building on property, and staff has increased personal protective equipment and performs more frequent glove changes.

“The biggest fear is a within-facility transmission,” Klebe said. “If you had something that contracted the disease here, that is the biggest fear because it means that there's a flaw in your biosecurity. It means that there was a way for the disease to transmit between patients.”

When transmission occurs within a facility, Klebe said the US Department of Agriculture becomes involved and often recommends depopulation, which involves euthanizing all of the birds in an area where there’s risk of transmission. She said that has never happened at the sanctuary, and it’s why biosecurity is so important.

Aside from the never-ending stream of patients, The World Bird Sanctuary also has to consider the dozens of birds that live at the rescue permanently - many of which are critically endangered species. Some of the sanctuary’s permanent residents include an Andean Condor - considered vulnerable in the wild - and two Vietnamese Pheasants, which are believed to be extinct in the wild due to Agent Orange, a defoliant used often during the Vietnam War..

Klebe said the resident birds are at a lower risk for contracting avian flu and so far none have displayed signs of the virus, but staff has implemented precautionary measures like regular shoe cleaning between enclosures to reduce the risk of spread.

“Whenever we enter any aviary, we're spraying the bottom of our shoes for anything that we've potentially stepped in, especially because wild waterfowl are one of the main carriers, and they do frequent the property. They poop on the property, we step in their poop whether we want to or not,” Klebe said. “So we're spraying the bottom of our shoes to prevent [tracking] that.”

Officials, rehabilitators say the public can help reduce the spread

Because raptors contract avian flu by eating infected prey, wildlife rehabilitators and state health officials alike have said members of the public should contact state agencies to report any dead birds they might see.

Hudman said MDC officials are coming out to remove and test bird carcasses for avian flu as a method of monitoring its spread throughout the state. Hudman and Klebe both said members of the public can also help protect raptors and other animals by safely removing and disposing of bird carcasses using proper protective equipment.

“So put on some gloves, double bag it, and we say double bag like you can put that bird at the bottom of bag and twist it, and then fold that bag back around itself - just again to prevent any kind of scavengers from getting to it - and then just put it in your normal trash. Certainly try not to handle it bare handed,” Hudman said.

As for birds that are injured or need medical attention, Klebe said people should still call the nearest wildlife rescue organization for assistance if they encounter an injured or downed bird. However, she said the sanctuary no longer asks people to handle the injured birds - instead, people are asked to take a video of the bird to determine if it’s displaying symptoms of avian flu.

“If we're having doubts, what we'll ask, instead of them trying to contain it, is to get just a cardboard box and put it over it. That keeps the bird from getting away by the time we get someone out there,” Klebe said.