The economic downturn caused by the coronavirus could roll back state investments in pre-K made since the last recession, including in Kansas and Missouri.

That’s the dire warning in the latest preschool yearbook from the National Institute for Early Education Research, which looks at state spending on pre-K during the 2018-19 school year.

“We know in the last recession, enrollment, spending and quality standards were cut, and that spending impacts continued well after the economic recovery was underway,” said NIEER director W. Steven Barnett. “In most states, pre-K is discretionary. But it needs to grow and improve, not just hold on.”

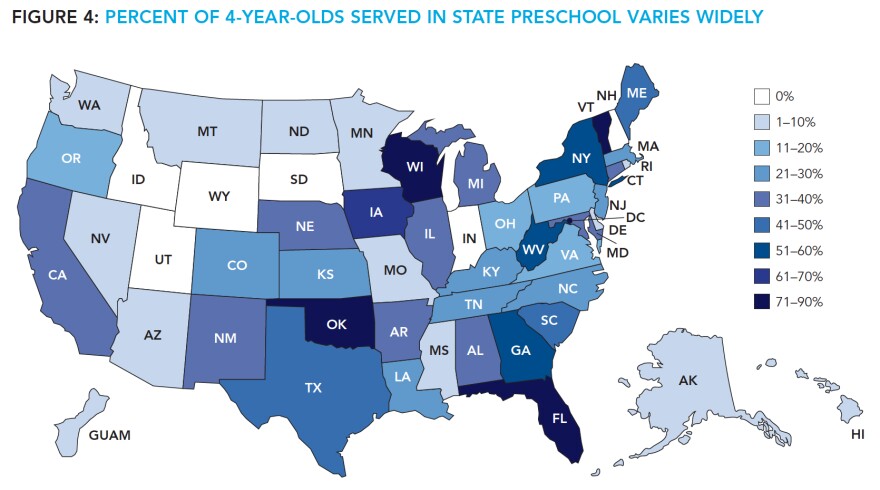

But in many states, there isn’t much to cut. In Missouri, for instance, just 6% of 4-year-olds and 1.5% of 3-year-olds were enrolled in state-funded pre-K last year.

Missouri makes incremental gains

Still, 6% is better than 2%, which is how many Missouri 4-year-olds were in state-funded pre-K in 2018. According to NIEER, Missouri added 3,410 preschool seats during the 2018-19 school year. NIEER also praised the state for meeting another quality benchmark – Missouri Preschool Program teachers and assistants all get at least 22 hours of professional development and coaching.

But the state is also moving away from the Missouri Preschool Program. Starting in 2018, school districts and charter schools could count pre-K attendance under the foundation formula, which is how K-12 education is funded in Missouri.

“Do you mean the foundation formula that doesn’t support normal programming?” former Kansas City Mayor Sly James scoffed.

James spent his last year in office campaigning for a sales tax to pay for pre-K. At the time, he said a sales tax was the only way to get every 4-year-old in the city into universal pre-K without state support.

“Your budget says exactly what you think is a priority, and this doesn’t say that (Missouri lawmakers) think that quality pre-K education for every kid in the state was a priority,” James said, reached by phone Tuesday to talk about the NIEER report.

Voters ultimately rejected James’ plan to pay for pre-K. One of the sticking points seemed to be how the $30 million the sales tax was projected to generate would be spent. Instead of paying for tuition, James’ plan called for an up-front investment in small child care providers so that they could improve quality.

Now James is worried that many of those “mom and pop” day cares won’t reopen after the pandemic. Though licensed child care is not the same as high-quality early childhood education, it’s often what families can afford in states without robust funding for public preschool.

“Women, particularly low wage-earning women, are going to be stuck with the consequences,” James said. “If they can go back to work, but the people who have provided them child care are no longer available, then can they really go back to work?”

Lessons learned in Kansas

Former Kansas state Rep. Melissa Rooker of Fairway is worried, too. She said few of the child care providers she works with at the state's Children’s Cabinet have been able to access coronavirus relief for small businesses.

“The small business program got gobbled up so quickly, and our providers aren’t equipped to have moved fast,” Rooker said. “They’re not set up with attorneys or accountants.”

Before the pandemic began, the Children’s Cabinet was working with the Kansas Department of Education to improve early learning opportunities. Rooker said that work will continue – as long as Kansas lawmakers don’t try to balance the budget with education cuts again.

“Between the resources made available by the federal government to address the COVID aftermath and the awareness our legislature has based on the past decade of financial struggles, I’m optimistic that early childhood education will be spared,” said Rooker, who served in the legislature from 2013 to 2018.

“We see such dramatic return on investment for the dollars invested in that developmental phase of a child's life," she said.

Rooker added that there’s bipartisan support for early childhood education in Kansas, a fact backed by the NIEER report. Between 2018 and 2019, pre-K spending in Kansas increased 24%, and the state leveraged federal Temporary Assistance For Needy Families dollars to boost per pupil spending significantly.

But because NIEER only factors in certain revenue streams, the 2019 report shows the percentage of Kansas 4-year-olds in state-funded pre-K seats declined from 26% from 36%, below the national average.

KSDE Director of Early Childhood Amanda Petersen said the number of Kansas kids being served in preschool programs, regardless of funding source, actually increased from 21,368 in 2018 to 23,513, which squares with the NIEER report.

“There’s no one funding stream that’s sufficient to pay for the cost of pre-K,” she said. “At the local level, districts are pulling together multiple funding sources to make their overall classroom budget work.”

COVID-19 could set pre-K back

Although pre-K access has expanded in the decade since the Great Recession, it’s not growing as fast as it was before. According to NIEER Director Barnett, in some states, cost-containment measures like bigger classes are still in effect.

That could be a problem if strict social distancing measures remain in effect at the start of the next school year.

“In Washington [state] right now, we’re down to 10 people in a room. The economics of child care – let alone the economics of pre-K – don’t make a lot of sense with nine kids in a room and one teacher,” said Washington Department of Children, Youth and Families Secretary Ross Hunter, who participated in a NIEER news conference on Monday.

Barnett put it more bluntly.

“Computer programs are not a substitute for real preschool,” he said.

Barnett said more families will be eligible for federal- and state-funded preschool as a result of coronavirus-related income loss.

Already, states are making cuts. Missouri Gov. Mike Parson reneged on more than $20 million in funding designated for education as he tried to balance the budget amid a sizable drop in tax revenue.

Former Kansas City Mayor Sly James said he’ll be disappointed, but not surprised, if funding for the state’s fledgling preschool system gets cut.

“The coronavirus has crystallized in the minds of more people the absolute divisions between socioeconomic groups and between races. The same patterns follow education as well," he said.

"We are going to continue to have these problems until we make sure that every child has an even start at birth."

St. Louis Public Radio's Ryan Delaney contributed to this report.

Copyright 2021 KCUR 89.3. To see more, visit KCUR 89.3. 9(MDA3OTgyNDI4MDEzMTM0MjQzMTZlNDI0Mg004))