Jonathan Verdejo has watched people come and go. His people. The ones he can play some of his favorite music to in his job as a DJ—and they’ll actually sing along.

Verdejo hosts various Latin Nights throughout Columbia. It’s frequented by students and locals alike. Their voices almost drown out the music.

"Si hay sol, hay playa. Si hay playa, hay alcohol..."

Verdejo said it’s become like a second home for people in a place where there aren’t many options to experience Latin culture. Only about 3.4 percent of his city identify as Hispanic or Latino. Verdejo, originally from Mexico City, moved to Columbia from Los Angeles, where a little more than 48 percent of the city identifies as Hispanic or Latino.

"It was definitely a big change. I mean, it almost felt like I was in a different country," he said. “And that's one thing that it's really hard for them (Latinos), is that there's nothing that they can connect with. And, you know, that's one of the reasons that I do what I do."

It’s not just Verdejo’s experience that there aren’t many Latino people in mid-Missouri. U.S. Census data shows Missouri actually has one of the lowest percentages of people who identify as Hispanic or Latino in the Midwest. It’s around five percent. That’s compared to Illinois at 17 percent, Kansas at 13 percent and Iowa at around seven percent.

So what gives?

In my experience, my Cuban family are some of the most friendly, welcoming and let’s face it, LOUD people. And it’s not just me.

“It's not simple. Everybody might be similar, but everybody's got different points of views, different things that they do," Verdejo said. "But there's a lot of similarities. And so that's what we focus on: the things that we can connect on.”

Verdejo and I embodied this sentiment—as we both sat for hours in a coffee shop even after the formal interview had ended, chatting about things like, how we both make sure other Spanish speakers around us know we understand them.

"So don't talk about me," I joked.

Verdejo laughed, brought two fingers to his eye line in the "I see you" symbol: "Ya te vi ya te vi" he said while still chuckling.

All jokes aside, a little more than 50 percent of the nation’s growth is from Latinos, which Missouri is lagging behind. Missouri’s percentage comes out right around 42.5 percent.

Ness Sandoval, a professor of demography and sociology at Saint Louis University, said there’s no question that Missouri needs to catch up with its neighbors in attracting the group that’s expected to be an integral part of the demographic makeup of the U.S.

I think that the part that's unknown is: Is Missouri going to fight?

“I think that the part that's unknown is: Is Missouri going to fight? And what I mean by 'fight,' go out and say we want Latinos to live in the state," Sandoval rhetorically asked.

One example of a neighbor's 'fight' in Illinois has materialized as a Latinx Outreach program through its Department of Human Services. One of the goals is to help Latinos in Illinois contribute independently to their communities.

As of now, the same sort of 'fight' hasn’t amounted to much in mid-Missouri.

Multiple advocates described a sort of resource desert for Spanish-speakers and for Latinos in general–especially in mid-Missouri where there are more rural towns.

There isn’t a way to major in Latino Studies at any of the University of Missouri branches. There are no federally designated Hispanic-Serving Institutions in the state—which means no schools have a student population that’s 25 percent Hispanic or Latino.

But la gente is trying.

One rural Missouri community has worked to unite the town and make sure Latinos feel welcome.

Maria Sanchez lives in Carthage where almost a third of the residents identify as Hispanic or Latino. She’s part of the group that founded Conexion Hispana/Hispanic Connection–with the goal of uniting the city. They organized their first Hispanic Heritage festival in the city last year.

When she first moved from California 17 years ago, Sanchez, a realtor of 20 years, was everywhere around town translating for all sorts of situations ranging from funeral homes to financial support, to health services and of course housing.

The need for more resources was so great, it resulted in a tragedy in Sanchez’s life. In her second year in Carthage, Sanchez's husband died in a construction accident which she describes was due to a language barrier.

"I had to raise my two kids on my own. So it was important for me to be even more involved in the community, to feel that warmth of family that I needed in order to stay happy in this area," she said.

Since then, she said the city has developed a lot.

“Now you have employees that work with the city. You have [a] police department that has Hispanics, Carthage Water has Hispanics, the fire department has a Hispanic. I mean, I've seen the growth," she said. "Before, you didn't have that. So now the comfort is there."

Conexion Hispana will have its second annual Hispanic Heritage Festival this September during Hispanic Heritage Month.

"In the past they (Hispanic heritage celebrations) were very minimal. [Carthage] would have them with some years here, some years there. But we don't want this to die," Sanchez said. "We want this to be a yearly thing from last year forward and, you know, make it something successful and pretty much unite the community."

'Tough road for Missouri'

There are more Latinos in mid and rural Missouri now than there were ten years ago. It doesn't quite match the same pattern as the country as a whole, and that's what demographer Ness Sandoval said needs to change. The state needs people to live in it, and the people who have growing communities are Hispanic and Latino populations.

This isn’t a cause for what Sandoval terms demographic anxiety—which is a common cause of so-called ‘replacement theory.’

The shift in demographics will make some changes to American culture, like possibly adding the 'ñ' to the official alphabet. But Sandoval said it’s not a bad thing.

“It is in our nature to change," he said. "So we should embrace it, not be afraid of the change.”

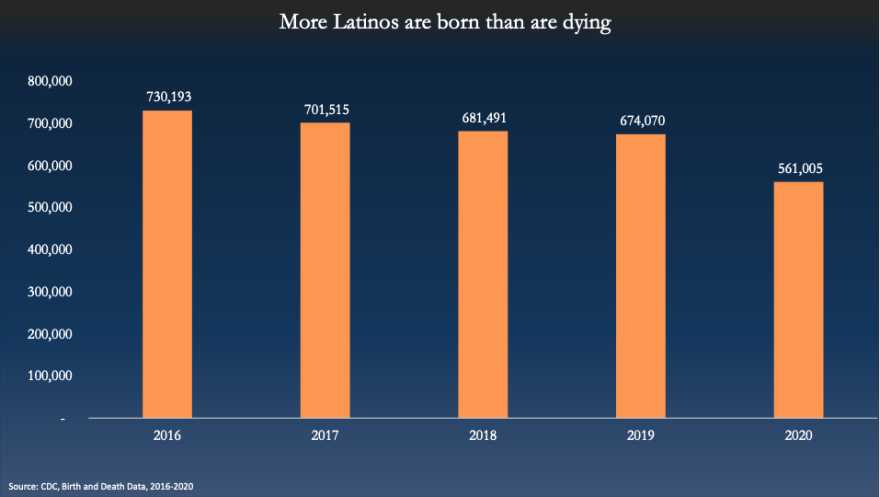

Just generally, Missouri and most of the Midwest is in what’s called a demographic winter: where more people are dying than are being born. If more Latinos don’t move to the state, Sandoval estimates it could lose a House seat, since Latinos are one of the bigger demographic groups actually growing.

“Missouri is not the only state in this circumstance. So you have other states who are in a demographic winter, who are saying 'We need more Latinos,' so it's gonna be a tough road for Missouri," Sandoval said.

So, it’s fair to say a lot depends on the relationship Missouri creates with Latino populations. In the following parts of ¿Dónde está mi gente?, I’ll look into how it looks currently, and what still needs to be done.

¿Dónde está mi gente? will continue with five more upcoming segments.

For the audio transcript, click here.