“I got to stay with her for 48 hours, and then my husband came to get her. It was the most eye opening experience that I've ever been through in my life – to have to leave her in the hospital.”

Tara Carroll has been incarcerated for several years. She was pregnant when she entered Vandalia Correctional Center as an expectant mom. Not long after, she gave birth to her daughter, Dylan Raye.

“And then, I promised her that I would do everything I could to become the best me and the best mom possible for her,” Carroll said.

"Of course, I'm excited to hold an infant. I love babies. Who doesn't love babies?"Caregiver Antoinette Rutschke

Until now, the only option for pregnant inmates, like Carroll, was having 24 to 48 hours with their newborn in the hospital. Then the baby went home with a caregiver and mom went back to her cell.

Dylan’s now 2 and a half. Carroll is doing her best to make good on her promise. She’s one of just six incarcerated women in the state selected to work in the new nursery within the Missouri Department of Corrections.

Back in 2022, Lawmakers passed a law to create the “Correctional Center Nursery Program” to address the issue of mothers being separated from their newborns at birth.

According to “Shackling and Separation: Motherhood in Prison,” an article published in the American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics, there are about 2,000 babies born each year in the United States to incarcerated women. This separation has been shown to have negative impacts on both the mothers and their children throughout their lives.

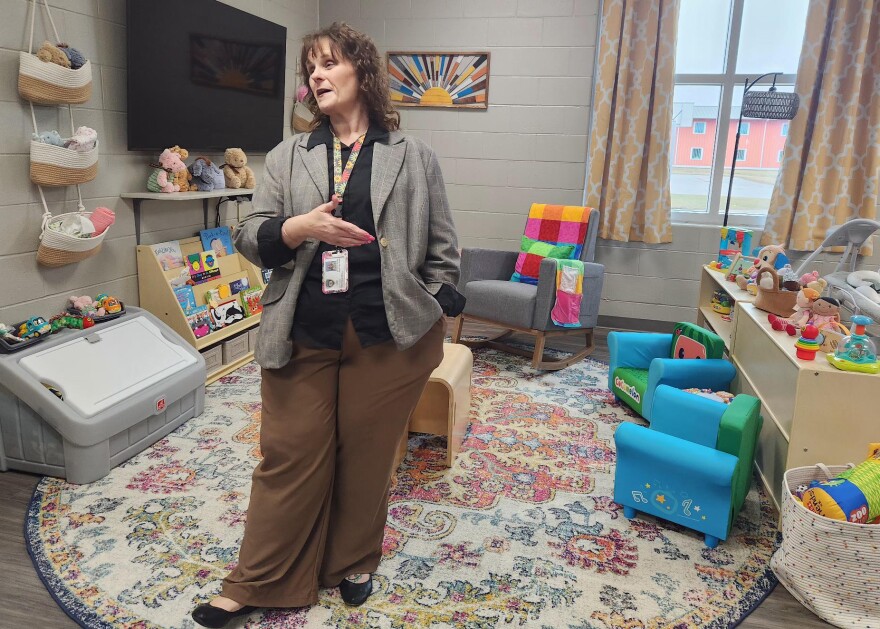

Kim Perkins, the new nursery program director, said the prison at Vandalia was doing what it could for new mothers. These efforts include providing postpartum medical care, giving mothers the opportunity to pump and store breastmilk and holding parenting classes. But still, separation can be devastating for these new moms.

“They have an opportunity now to have that bond. To be able to breastfeed, to be able to have a sleepless night because their baby's crying, and experience all those things within a safe environment,” Perkins said. “It's secure, and they have people around them who are here to help them and encourage them in that journey, so they're not just left out to do it by themselves.”

The new facility, which opened in late January is now expecting its first mothers. It’s in a completely separate, converted wing of the prison. And instead of blank white cement walls and floors, the unit is decorated with calming shades of gray and blue.

The facility can hold up to 14 infants at a time, which may not equal 14 moms, as the nursery is expecting a set of twins. Each mother will be given a separate room with state-of-the-art baby gear, such as cribs, a pack and play, a rocking chair, colorful rugs on the floor and art on the walls that doubles as soundproofing.

“We have a daycare center, we have a day room, we have an educational room here, so mom can do classes here,” Perkins said. “We try to bring everybody we can here. Mom can also do treatment on this house. So, if she is court ordered to treatment, she can do that while she's still incarcerated and still being a mom.”

Not all expectant inmates are eligible for the nursery. They can’t have violent felonies, sex offenses or crimes against children. Women also have to be within 18 months of release to ensure that moms and babies can bond during that important early development stage, as well as make sure babies are getting the socialization they need outside of prison as they enter their second year of life.

“Because we want mom to be able to go home with baby, and so, that's the whole purpose, is that bonding process happens and we don't have to tear them apart again,” Perkins said.

The facility is designed to maximize success and simulate motherhood outside prison walls. Perkins said they’ve even hired correctional officers who work specifically on the new unit who are prepared for inmates wandering around the unit at any time of the night, since babies aren't known to be good with curfews.

She added the nursery wing at the Correctional Center in Vandalia expects 40 babies to come through the nursery each year, and moms will leave the nursery with baby books and family pictures, infant clothing, formula, a pack n’ play, a car seat, a stroller, and at least a month’s worth of diapers.

As Perkins put it, “all those necessities that they can go out and be successful with.”

Providing care to mothers and themselves

The nursery also hired caregivers from within the incarcerated population to assist the moms, when needed, like Tara Carroll. The six women all come from different walks of life – young mothers, moms with grown kids, beloved aunts, grandma and more.

Rheaya Goodwin, or “TT” to her nieces and nephews, has been incarcerated for a few years and sees the parole board next June. She moved from Chillicothe Correctional Facility to join the new program, which she said has given her a new sense of purpose.

She said the caregivers moved into the unit a few months ago and have spent their time putting together baby furniture and readying the unit.

“I am here for a reason – ready for babies. The hard part is over. We made it through the selection process. We made it through the interviews. We made it through moving from Chillicothe back to Vandalia. We made it through splinters in our fingers and crawling into bed with every bone in our body sore. We made it through that,” Goodwin said. “Now it's time to let the community know and the legislatures know that this was not a mistake, this was not something that they're going to regret.”

The team of caregivers also spent a lot of time in classes learning how they can best help moms – both inside the unit, and even before making it through the selection process.

Classes have included topics such as CPR, safe food preparation, effective parenthood, and the basics of trauma-informed care.

Goodwin called these classes a “godsend” because the certifications are something she can take with her that will help her succeed in whatever she decides to do upon release.

Brianna Johnson is another of the caregivers. She is a mom herself, but her daughter is now in college.

She said after prison she’d like to go into peer support – helping folks with substance use disorder or even the impacts of toxic stress on children.

But for now, she said she's looking forward to helping their moms learn from the mistakes she made in the past.

“If I can do anything to give another young woman the opportunity to see the error of her ways to where she doesn't do the same things that I had to do to get to where I'm at 40 years old – then that's what I want to do,” Johnson said. “I'm extremely passionate about inspiring hope in these women and giving them the care that they need to be mothers, not to care for their children for them, but to inspire them to care for their children for themselves.”

Caregiver Antoinette Rutschke is also ready to share the experiences she’s gained from raising five kids and helping children throughout her neighborhood.

Rutschke left a work release program in Chillicothe to join the nursery staff because she’s passionate about giving back to others. She added that she hopes this program can set her on the path of earning a CNA license.

“Of course, I'm excited to hold an infant. I love babies. Who doesn't love babies?” Rutschke said. “I think my heart is with the mothers and hoping that from my past experiences and mistakes that I can maybe help them through some things that they're going through.”

Kendra Riggs is also passionate about helping moms – especially those who might feel a little lost and disconnected in the early stages of parenthood.

She said that “being a mom doesn't come with an instruction manual,” which is why she thinks the model of community care and shared responsibility in the nursery will be so beneficial to baby and mom.

“I'm just hoping that when they leave here, they want to be the mom,” Riggs said.

Riggs added that she’s sure the work will be hard, but there are other benefits to working in the nursery unit. Caregivers get to live in a much more private space than the rest of the prison population, they get two mattresses and better bedding, and have access to simple things – like an air fryer.

Riggs said – besides the babies, of course – it’s the direct connection to staff and the trust of nursery leadership that she’s most excited to have access to.

Tara Carroll is the only member of the caregiving staff that gave birth – and was separated from her newborn – while incarcerated at Vandalia.

She said she knew right away that she had to be involved in the nursery program.

She said the women on her mind right now are women like her – who didn’t have the option of the nursery.

“Because I understand how painful it's going to be for the moms that don't qualify to come to this program,” Carroll said. “And so, we as caregivers are here for all of the moms, all the women that come in pregnant on this camp. We're here for all of them to give them a better support system, because I feel like that's something that was lacking.”

Carroll said she’s had long conversations with her husband about whether or not working in the nursery is going to be healing or harmful to her – since she’s missed so much of her own daughter growing up.

But, in the end, she says that’s part of why she applied to be on the nursery staff. She said those hard moments will remind her what’s working toward.

“I'm doing this not just to help these moms, but so that when it is time for me to go home and be a mom, I'm the best mom to my daughter that I can be,” Carroll said.